articles #article

Street of Crocodiles, or the existential interpretation of the mechanized bodies

What philosophical implications does entering metauniverses entail? What is the role of the body in these processes and our relationship with reality? What mechanisms intervene in these links? These and other questions are explored in this text, which addresses one of the emblematic works of animation from the last quarter of the 20th century: Street of Crocodiles (1986) by Stephen Quay and Timothy Quay. This analysis seeks to delve into the relationship between the subject, (meta-)reality, and the Other from the corporeal-existential perspective of J.P. Sartre, with the aim of rethinking our present, characterized by the interpersonal proximity-indifference paradox mediated by digital culture.

One of the most important debates of the actuality resides on the virtual experience of the subjectivities: what advantages/disadvantages does participation in metauniverses entail, what we gain and what we lose in this process, in what ways subjectivity is affected. Not a few philosophers or scientists have attempted to respond to these questions and have reached not encouraging answers: digital universes can only offer imitations of the world, not real ones, but simulacrums.

From the perspective of film animation, this problem has been questioned for several decades. A clear example of the philosophical risks involved in the access to alternate universes —digital metauniverses— can be found in Street of Crocodiles (Quay Bros., dirs., 1986): an artistic piece that deals with what we lose when we integrate into other worlds and we attempt to understand them.

In this text, I propose to analyze this film based on Jean-Paul Sartre's existentialist conceptualizations of the body as a means of existential rectification and a relational vehicle with the Other. The primary objective guiding this investigative work is to establish aesthetic-philosophical bridges that highlight the importance of the body as a means of problematizing individual and collective existence, with special attention to the process of mechanization of the subject in postmodern societies. To address these objectives, I will follow the following method: first, I will allude to the allegorical significance of the film strategies employed by the Quays; then, I will investigate the link between the individual and his body; then, I will explore the problematic coexistence of the subject with the Other based on Sartrean sadism; finally, I will show how, as a result of this coexistence, the film highlights the depersonalizing effects that the postmodern world exerts on the individual. The relevance of approaching this work from this perspective lies in the fact that it updates it and places it at the center of the dialogue on contemporary issues surrounding the role of subjectivity in digital/virtual cultures.

Street of Crocodiles is part of the postmodernist paradigm of cinema (León Frías, 2022)1 by presenting a metanarrative strategy from the beginning, showing a man entering an empty theater; he then reaches a kinetoscope and spits into it, which initiates the narrative action within it (that is, a diegetic universe within another). The action that occurs inside this artifact is the main action of the film. This other narrative plane begins when the man in the theater cuts the strings of the puppet (protagonist). Now, an allegorical reading allows us to decipher these signs as the instant in which the subject is thrown into existence. The man at the beginning could be an allegory of God or an artistic creator, and the work is the puppet-humanity. In other words, the puppet represents humanity, whose universe is delimited by a multidimensional room with four walls and secret passages.

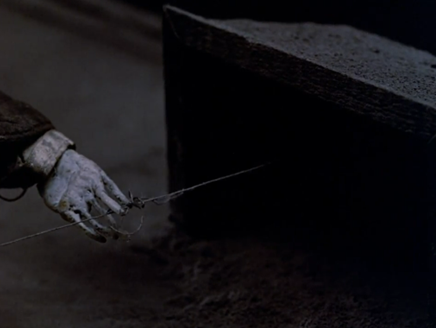

Street of Crocodiles (Quay Bros., dirs., 1986), 00:02:13.

This throwing into the world occurs when the protagonist's ties to God are severed and he must (re)cognize his world: the subject loses all metaphysical anchorage and must confront the universe on his own. At the beginning of this process, the subject encounters his reflection, an imitation of who he is, how he presents himself to others, an aspect that the Quays problematize later in the film. It is at this point that his interaction with reality has a corporeal origin, since it is through his corporeality that he confirms that he exists and occurs in a ruined and problematic space. Thus, similar to Antoine Roquentin, protagonist of Sartre's Nausea (1938), the puppet doubts and rectifies that he exists through his body, although the link he forms with the world is still diffuse and inexplicable: „I stopped short because I felt in my hand a cold object which held my attention through a sort of personality. I opened my hand, looked: I was simply holding the door-knob.“ (Sartre, 15)

Now, the functions of the puppet's body are not limited to rectifying its empirical existence, but rather order its universal experience in a unique way: they constitute an episteme in which, faced with the hostility of the new world, chaos is ordered specifically for him. This can be seen when the protagonist unravels the symbolic thread that, at the same time, constitutes the entrance to the third narrative level of the play: the Street of Crocodiles. In other words, the unraveling and drawing back of the curtain can be read as the ordering of the world through the body, as Sartre mentions in Being and Nothingness (1943): „This absolutely necessary and totally unjustifiable order of the things of the world, this order which is myself in so far as I am neither the foundation of my being nor the foundation of a particular being-this order is the body as it is on the level of the for-itself“ (309); that is, universal chaos is ordered under our sensorial and intellectual perception and interpretation. In fact, one is the necessary condition of the other: without the subject, this form of universal event does not exist, and vice versa.

Street of Crocodiles (Quay Bros., dirs., 1986), 00:03:04.

From the moment the protagonist enters the Street of Crocodiles, he feels vulnerable, excitable, and curious about his surroundings, whose characteristics are those of a totalitarian postmodern society, with its necessary paradoxes. This new setting reveals the fragmented, encapsulated, estranged from one another, yet at the same time perpetually exposed to the Other. There, time is measured by the deterioration of the physical body; it is a space of infertility and lack of communication, where everything is mechanized, dirty, diffuse and withered. To emphasise this topography, the Quays abandon verbal language and appeal to the aesthetics of the grotesque, a notable aspect of their entire filmography that has influenced multiple audiovisual creators: from Tim Burton to music video directors such as Floria Sigismondi with The Beautiful People (1996).

After the main character realizes where he exists, he begins to interact with the others, beings who are incarnations of the Bakhtinian grotesque: adult bodies with childlike faces.2 These inhabitants are mostly mannequins, whose movements always follow a fixed pattern; each member knows only one trajectory, and they have no freedom other than that afforded by the small capsule they inhabit. In other words, the Crocodile Streets represent absolute depersonalisation.

Upon encountering these beings, the puppet's fears materialize, as they lead him to a kind of tailor's shop to be tailored to their exact measurements. This is one of the central sequences of the film's anti-totalitarian discourse: the protagonist, driven by curiosity, tries to understand the functioning of this new world he has entered, but in the process he becomes corrupted and, upon seeing his body modified, loses its uniqueness, which puts his very existence at risk, as it becomes a mere reflection of its own mechanization. This is a sadistic operation that, in Sartre's terms, is defined as the fact that „the sadist's effort is to ensnare the Other in his flesh by means of violence and pain, by appropriating the Other's body [...] This is why the sadist will want manifest proofs of this enslavement of the Other's freedom through the flesh. He will aim at making the Other ask for pardon, he will use torture and threats to force the Other to humiliate himself“ (Sartre, 403). In this sense, not only the puppet's physiognomy is altered, but also its own vision of the world.

Street of Crocodiles (Quay Bros., dirs., 1986), 00:17:48.

In this way, Street of Crocodiles problematizes the sadistic mechanisms used in postmodern societies to appropriate bodies and, at the same time, the way contemporary subjects experience. However, the film differs from the methods, but not the purposes, mentioned by Sartre, since it exhibits the functioning of another type of violation —soft power— that makes the subject believe he is safe by returning him to the narrative background, that is, removing him from Street of Crocodiles. In this way, the strategies of depersonalization make “[a] movement may become mechanical. In this case the body always forms part of an ensemble which justifies it but in the capacity of a pure instrument; its transcendence-transcended disappears, and along with it the situation disappears as the lateral over-determination of the instrumental-objects of my universe.” (Sartre, 401). That is to say, current life simulation scenarios generate in the subject an illusory state of belonging to a universe; however, they accentuate its mechanization and contribute to the lack of understanding between the individual, his world, and the Other, where the highest aspiration is to observe the undifferentiated collective body in a mirror —a screen—.

Throughout this text, we have seen how, despite the fact that nearly four decades have passed since its premiere, Street of Crocodiles is a testament to the current era, in that it allegorically thematizes the relational processes between the subject, the metauniverses, and the Other. First, we alluded to the powers of the individual's body as a means of ordering the world: the way in which reality occurs is subordinated to the body, to the point that the body constitutes the means by which the individual confirms his existence, such that sentio, ego sum. Then, we explored the conflictual link between the subject and the Other based on the transgression and violation of the body through Sartrean sadism, where the aim is to appropriate the physical uniqueness —body— of the subject and thereby suppress its freedom, which leads to its mechanization. Finally, some features of contemporary sadism employed in metauniverses were raised based on the reflections that the Quays present in Street of Crocodiles, with which we seek to expand the discussions on the subject from film theory in general and animation theory in particular.

Francisco Tinajero (CDMX, 1999): He studied Hispanic Language and Literature at the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, UNAM. He holds a diploma in Film Theory and Analysis (UAM-Xochimilco in collaboration with the Cineteca Nacional).

1 Del clasicismo a las modernidades. Estéticas en tensión en la historia del cine, 437-445 pp.

2 Vid. Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World. Indiana University Press, trad. Helene Iswolsky, 1984, 484 pp.

References.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World. Indiana University Press, trad. Helene Iswolsky, 1984, 484 pp.

León Frías, Isaac. Del clasicismo a las modernidades. Estéticas en tensión en la historia del cine. Universidad de Lima, Fondo Editorial, 2022, 513 pp.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. Being and Nothingness: An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology. Routledge, trad. Sarah Richmond, 2018, 918 pp.

_____. Nausea. Penguin, trad. Robert Baldick, 2000, 240 pp.

Stephen Quay and Timothy Quay, directors. Street of Crocodiles. Screenwriters Stephen Quay and Timothy Quay, Atelier Koninck, 1986.