articles #interview

Mohamed Ghazala: Vibrant and growing African animation

African animation – what does this term actually mean? What is its history, and what does it look like today? These are the questions explored in an interview with theorist, educator, and director Mohamed Ghazala, who also serves as a juror at the Anifilm 2024 festival. In the conversation, he highlights key moments and essential films. And how does Disney’s The Lion King fit into all of this? The interview is available in both English and Czech.

I would like to start with an apparently simple but actually complex question: What is African animation?

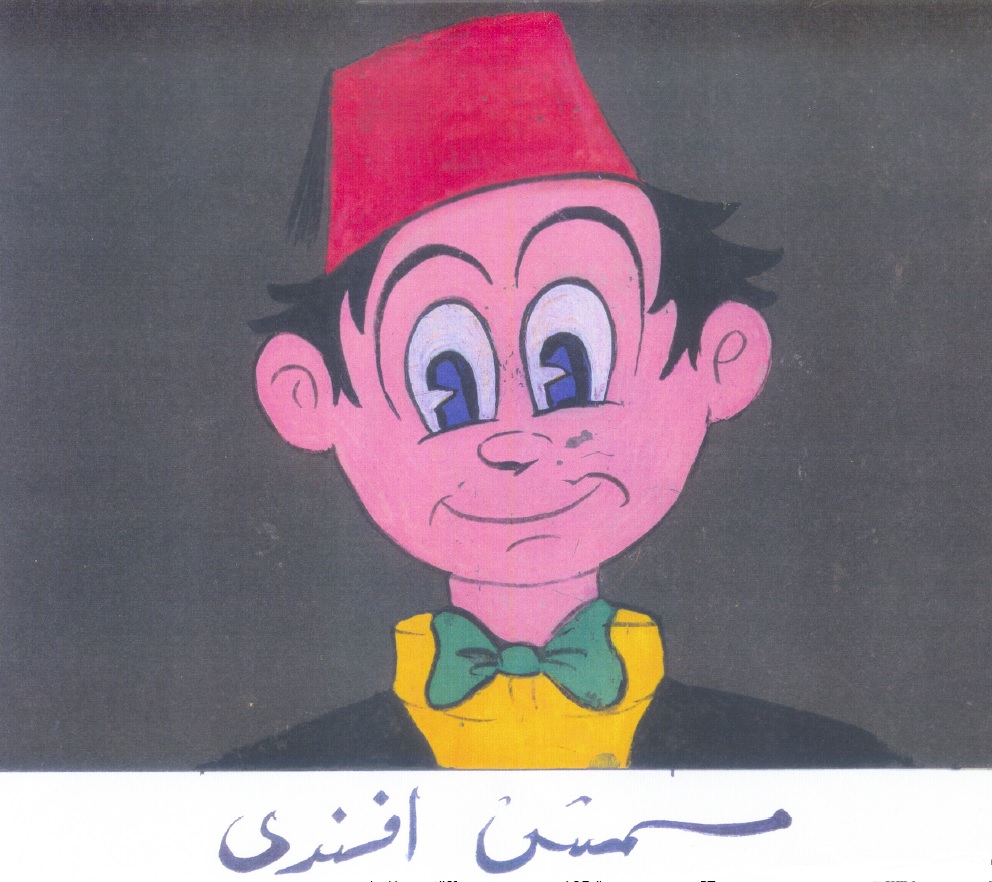

Many people are unaware of Africa's contributions to animation, much like how they may not recognize Mish Mish Effendi, an African counterpart to Disney's Mickey Mouse that has been around since the 1930s.

Defining African animation is really complex, as it includes criteria like production location, creator nationality, funding sources, and target audience. Some definitions extend to works by non-Africans created in Africa, such as the American Harold Shaw’s The Artist’s Dream, considered the first animated film produced there in 1915.

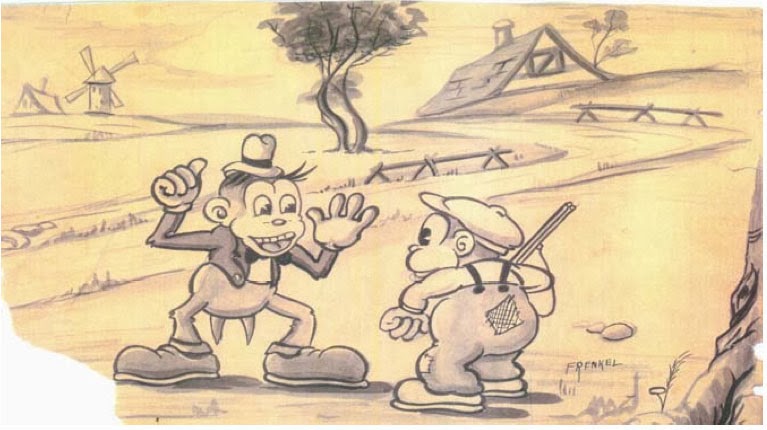

The character Mish Mish Effendi, created by the Belarusian Frenkel brothers with partial funding from the Egyptian government during World War II, further complicates the definition. Some historians argue that African animation should consist of works by African-born individuals, regardless of ethnicity, recognising the Moheeb brothers as the first African animators with their 1962 film The White Line. Other key early works include Moustapha Alassane’s Aouré and Mohamed Aram’s The Feast of the Tree, both from 1963.

Giannalberto Bendazzi suggests that historical narratives may evolve; the origins of African animation could date back to the 1930s with the Frenkel brothers. Ultimately, many historians agree that multiple perspectives shape film history.

African animation is celebrating its 90th anniversary — what is considered its beginning?

The origins of African animation can be traced back nearly 90 years to Egypt, where the Frenkel brothers—Belarusian carpenters who immigrated in search of work and freedom—founded the industry. Despite facing challenges with funding and equipment, they produced Africa's first animated film, Marco, the Monkey in 1935. Unfortunately, this two-minute film was later lost. However, their second film, “In Vain” of 1936, still exists.

Over the years, many individuals across Africa have made significant contributions to the field of animation. Notable figures include Mustafa Alassane from Niger, the Moheeb brothers and Ihab Shaker from Egypt, Mohamed Aram from Algeria, and William Kentridge from South Africa. However, these efforts often remain isolated and do not form a cohesive industry comparable to global movements like Japanese anime or American cartoons.

What is African animation like today?

Economic challenges in Africa complicate the development of a thriving animation industry, as producing high-quality animation requires significant resources and collaboration. Nonetheless, since the rise of the internet, we have started to witness the emergence of remarkable works in the new millennium, along with many success stories from across the continent.

In recent years, animation in Africa has flourished into a vibrant and growing industry. Driven by technological advancements and the passion of talented artists, African animation has started to gain recognition and captivate audiences both locally and internationally and it has become open for co-production with international companies.

What themes resonate in African animation today, and why? Has it evolved over time?

The concept of African animation involves several key considerations, particularly regarding what elements are deemed representative of Africa in terms of animation techniques. For instance, Jock of the Bushveld (2011) tells a uniquely African story, situated within a specific historical, cultural, and literary context that unmistakably identifies it as such. Similarly, Zambezia (2012) features iconography, such as animals and landscapes, that can be associated with Africa. While these examples showcase productions originating from Africa, created by African companies and leveraging local expertise, the question remains whether a design aesthetic can be distinctly labeled as "African." Generally, many commercial television series in North Africa tend to focus on traditional, social, or religious narratives, often employing local themes and humor.

How should African animation be viewed in the global context? Does it adopt foreign influences, and does it influence the world in return?

The story behind one of Disney’s most iconic films, The Lion King, is a fascinating journey of creativity and discovery. After spending six months immersing themselves in the lush jungles of Kenya, members of the artistic team dedicated to this project sketched a variety of animals and landscapes, hoping to capture the essence of Africa in animation. Originally titled "King of the Jungle," the title was changed to The Lion King when the team realized that their setting was more accurately represented by the vast and open African savannah, with its unique ecosystem and wildlife.

Released in 1994, The Lion King is often hailed as a pivotal achievement in the "Disney Renaissance," a period marked by a revival of animated films that combined storytelling, music, and artistry in groundbreaking ways. The film's impact on popular culture is profound, resonating with audiences around the world and delivering timeless themes of identity, friendship, and the circle of life. This narrative illustrates how Africa serves as a powerful source of inspiration for captivating stories and remarkable films like The Lion King, showcasing the continent's rich heritage and diverse landscapes.

Is it open for co-production?

The growing number of animation studios across the African continent is a notable trend, with nearly one-third of co-production pitch projects originating from Africa-based studios. Some prominent titles include Ama Adi-Dako’s Drumland, Jérémie Becquer and Julien Becquer’s Mia Moké, Esmail Zalat’s The Prey, and Kay Carmichael’s Troll Girl. These projects showcase studios from countries such as Ghana, Senegal, Cameroon, Egypt, and South Africa.

This industry growth is further highlighted by the Disney+ anthology series Kizazi Moto: Generation Fire, which focuses on African futurism and features work from various animation studios across the continent.

Does African animation lean toward particular animation techniques?

In the early days of African animation, pioneers relied heavily on traditional techniques, such as hand-drawing images and filming them frame by frame. These methods also included stop motion animation, where objects are physically manipulated in small increments between individually photographed frames. This labor-intensive process laid the foundation for storytelling through animation in Africa.

As technology progressed, the introduction of digital platforms transformed the animation landscape. Many animators began to embrace paperless artistry, moving away from physical materials and utilizing computers for their creative processes. Today, these digital artists are capable of producing a variety of animated content—ranging from 2D animations to intricate 3D designs and interactive games—by harnessing cloud technology. This shift not only enhances efficiency but also allows for greater collaboration, enabling artists from different regions to work together seamlessly, thus expanding the creative possibilities in African animation.

You also focus on animation in the Arab world — what can you tell us about it?

There is actually a similarity between the history of animation in Africa and the Arab world, as at least half of the Arab countries are also located in Africa, with Egypt positioned at the center. The 90th anniversary is relevant to African, Arab, and, of course, Egyptian animation.

In general, the challenges facing animators in both regions are somewhat similar, particularly because the economic conditions are closely aligned, as both are developing countries. In my academic work, I aimed to explore the histories of animation in both regions and uncover the hidden gems of animated films produced in Africa.

During my travels across many African countries and almost all Arab nations, I encountered talented animators who felt hesitant to showcase their work publicly or submit it to festivals. This motivated me, as an academic, to help bring these artworks and filmmakers into the spotlight. I strive to support them in submitting their works to festivals and encourage them to communicate confidently with a wider audience.

Are you the first researcher to explore African and Arab animation on such a wide scale? What sources did you primarily draw upon?

I’m not first, but perhaps more active internationally. My main resource is the African animator himself, along with his relatives or close circle of friends.

You describe yourself as a filmmaker who teaches. How do you see yourself — more as a practitioner who theorizes or a theorist who practices? How do theory and practice connect in your work? What is your approach to teaching?

Socrates once said, „I cannot teach anyone anything; I can only make them think“ As a dedicated teacher, I am passionate about providing engaging and challenging learning experiences that help students achieve their goals through animation. I believe that every student deserves access to quality education, which enables them to become productive members of society.

I adopt a holistic and flexible teaching approach, recognizing that there is no one-size-fits-all method. Understanding my students' diverse backgrounds, cultures, and abilities is essential for creating inclusive and effective learning experiences.

I implement a variety of teaching strategies that emphasize engaged learning, communication, literacy, numeracy, collaboration, and problem-solving while incorporating a range of technologies.

What opportunities does the university where you work offer to animation students?

Since 2013, the School of Cinematic Arts at Effat University have pioneered the first dedicated animation program in Saudi Arabia. Our curriculum is based on the esteemed animation program from the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts. Over the years, we have meticulously refined and adapted this program to better fit the cultural and educational needs of our students, providing them with a solid foundation in both the technical and artistic aspects of animation. This commitment to excellence has helped us cultivate a new generation of talented animators who are well-equipped to contribute to the growing creative industry in the region.

What educational opportunities are available for studying animation in African countries?

Currently, there are only a limited number of academic institutions dedicated to the study of animation in a few African countries. While these programs do contribute to the field, I believe they are inadequate for fostering the growth and development of the African animation industry as a whole. To truly advance this vibrant creative sector, we need a broader range of educational opportunities, including specialized training programs, workshops, and partnerships with industry professionals. This would not only cultivate local talent but also encourage innovation and collaboration within the industry, ultimately enhancing the global presence of African animation.

You are also the vice president of ASIFA. Could you tell us about the association’s current activities?

ASIFA, the Association Internationale du Film d'Animation, has proudly stood as the largest animation network in the world since its establishment in 1960. With members from various countries, ASIFA fosters collaboration, support, and recognition within the animation community. This year, as it celebrates its 65th anniversary, the organization reflects on its rich history and contributions to the art of animation, promoting creativity and innovation in an ever-evolving industry. Activities and events commemorating this milestone are set to bring together animators, filmmakers, and enthusiasts to honor the past and inspire the future of animation.

What is your personal approach to animation as a creator?

Enjoy recording my dreams visually.

Are you currently involved in any new projects, whether a film or research?

Yes, new film, fingers crossed!

______________________________________________________________________

Mohamed Ghazala is an Egyptian associate professor of animation and the chair of the Cinematic Arts School at Effat University in Saudi Arabia. In addition to his academic role, he serves as the Vice President of the International Animated Film Association, ASIFA. He founded its first chapter in Africa and the Arab world.

He has served as a jury member for various international Film & Animation festivals, including Animafest Zagreb (2023), Annecy (2021), Stuttgart (2011) besides many other festivals globally.

Ghazala has directed and co-directed many award-winning films, such as Carnival (2001), Crazy Works (2002), HM HM (2005), Sayari Yetu (2006), including the first Yemen animated film Salma in 2006. Honyan’s Shoe (2009), which won the Animation Prize at The African Movie Academy Awards in Nigeria in 2010. At the Red Sea International Film Festival, his recent film The Pyramid received its world premiere and was later nominated for AMAA 2021. It won the top animation award at the Egyptian National Film Festival, among other international awards and recognitions.

In 2011, his first book Animation in the Arab World was published in Germany. His second book, Animation in Africa, was initially published in Egypt in 2013 and republished in 2021.

Festival Anifilm takes place in Liberec 6.–11. May 2025.

Jury Programme – Mohamed Ghazala: 90 Years of Animation in Africa / Thursday 8. 5. 2025 / 16:30 / Malé Theatre

Masterclass – Mohamed Ghazala: A Closer Look at Animation in Africa / Friday 9. 5. 2025 / 18:00 / Grandhotel Zlatý Lev